The ancient Romans most certainly had specific dog breeds, and their large fighting dogs were well recorded in art, sculpture, and literature. The Romans also had lap dogs, and Pliny, writing in the first century AD, wrote this about the Maltese so favored by the Roman women in his time (the quote was translated by Philemon Holland in the 17th century):

“As touching the pretty little dogs that our dainty dames make so much of called Melitaei in Latin, if they be ever and anon kept close unto the stomach, the ease the pain thereof.”

Europeans that came later also thought the Maltese had the ability to cure people of disease, and it was common practice to place one on the pillow of a person suffering an illness.

Roman Emperor Claudius, and Publius, the Roman governor of Malta, were each known to own a Maltese, but ancient Egypt also knew the breed since the earliest known representation of the Maltese was found on artifacts unearthed at Fayum, Egypt (600-300 B.C.). Representations suggest that Maltese were worshipped by the Egyptians. But wait, there’s more!

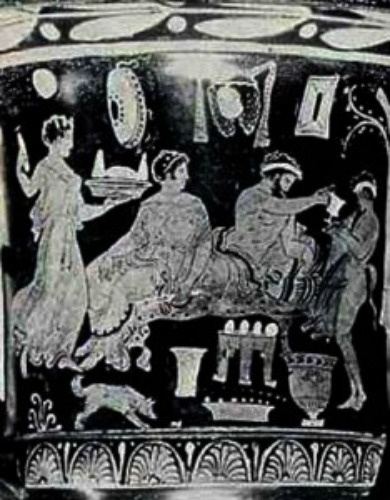

Pictorial representations of the Maltese were also found on Greek vases found at Vulci (about 500 B.C.). Even before Pliny, Aristotle was the first to make written accounts of the Maltese around the time of 370 B.C. when he mentioned Melitaei Catelli, and compares the dog to a mustelid. The dog was also mentioned by many ancient poets and historians, including Timon, Callimachus, Aelian, Artimidorus, Epaminodus, Martial, Strabo, and Saint Clement of Alexandria.

The Maltese. She got around.

Image believed to be a 2500-year-old Greek vase from Vulci that comes from Athenian school