Many years ago, we spotted a sighthound running like the wind in a place it shouldn’t have been at all, let alone running. We were leaving a dog show, and the dog seemed lost. From our car, we called the only person we knew in the breed to sound the alarm. Her words just before we hung up were, “Don’t run after him.”

She knew that we knew better than to chase a sighthound, but like a parent warning their kid not to run with scissors, it was a knee-jerk reaction. The anecdote has a happy ending. The dog had slipped his collar after being startled by a loud noise, and we were close enough to the fairgrounds that the owner was able to quickly get to where we were. To our amazement and relief, he ran into a fenced baseball field. As we (and by now, other good Samaritans) blocked the entrance to the field, we watched the dog “run the bases.”

He was poetry in motion.

But dog people can’t help themselves. We tend to look beyond a flowing coat to see a streamlined extension, and efficiency of movement. And with this “base running” hound, we were mesmerized by his tail, of all things.

When watching a sighthound in action, whether it’s at a FastCAT or coursing event, it is easy for a casual dog owner to assume that the long, sweeping tail is crucial for balance and agility – and for years, breed enthusiasts and even some breed standards agreed. The belief was that the tail provides stability while running and in sharp turns. The idea is intuitive: the dog runs and turns, the tail swings in the opposite direction, and it serves as a counterweight to help the animal maintain its center of gravity.

Some research has suggested that the tail’s role in communication is significant, but the physical function of the tail as a counterweight remains a compelling and observable aspect of sighthound locomotion.

When a sighthound accelerates or changes direction, the tail swings in the opposite direction of the turn. This movement acts as a counterweight, helping to stabilize the body and maintain balance. The tail’s position and motion can subtly shift the animal’s center of gravity, allowing for tighter turns and greater control at high speeds. Observers often note that, during a sharp maneuver, the tail is not passive—it actively participates in the dog’s ability to stay upright and agile.

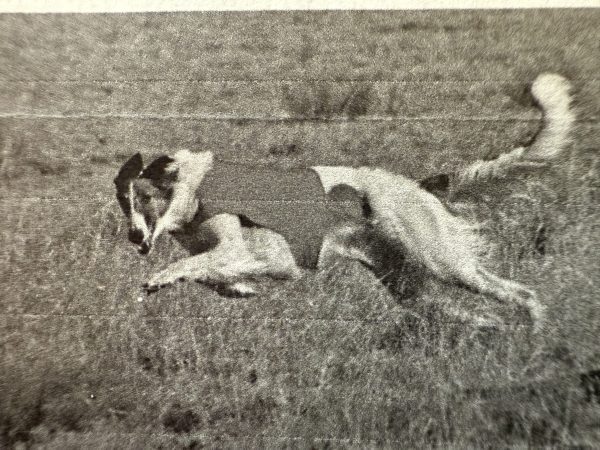

A photo of an image on a computer screen is never optimal, but the photo that “Elaine” shared with us back in 2017 was the best picture we’d gotten of a tail being used as counterbalance.

This counterbalancing function is especially important for sighthounds, whose long, low-set tails are adapted for pursuit across open terrain. The tail’s length and flexibility provide leverage, enabling the dog to make rapid adjustments in direction without losing stability. Even at a walk or trot, the tail can be seen making minor corrections, but its role becomes most apparent during running and sudden turns.

An alternative finding came with several studies including the 2022 research by the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems. Their study, titled “Dogs move their tails, but not for balance,” used motion capture and biomechanical modeling to analyze the tail’s role in canine movement. The researchers found that, for most dogs, the tail’s impact on the center of mass during running and turning was minimal. The study did acknowledge that the tail can provide fine-tuned adjustments—what they described as “trim”—that help with minute corrections in movement, but perhaps not as much as previously thought?

Anecdotally, experienced handlers and enthusiasts consistently report that their sighthound breeds rely on their tails for balance, especially during high-speed chases and sharp turns. The tail’s movement is coordinated with the rest of the body, acting as a natural stabilizer. This is not merely casual observance. It seems to be supported by the physical design of sighthounds, whose tails are specifically shaped and positioned to aid in athletic performance.

For sighthounds, whose tails are proportionally longer and more flexible than those of many other breeds, these subtle adjustments may be more pronounced. The visible swing of the tail during a turn, while not dramatically shifting the center of gravity, likely contributes to the dog’s ability to maintain balance and execute precise maneuvers. The Planck study didn’t negate the counterbalancing function entirely; rather, it suggested that the effect is more nuanced and breed-dependent.

Another study, Single limb dynamics of jumping turns in dogs – Katja Söhnel et al., Research in Veterinary Science, 2021 analyzed how dogs execute jumping turns, focusing on the forces and limb dynamics involved. Using advanced motion capture and force plates, the researchers found that turning during jumps is primarily managed by the limbs—especially the outer limbs, which generate about twice the force of the inner limbs in both vertical and lateral directions. The tail was not identified as a significant factor in balance or turning; instead, the study highlights that limb mechanics, particularly the asymmetry between inner and outer limbs, are the main contributors to agility and stability during complex maneuvers like jumping turns.

In the end, a sighthound’s tail remains a captivating feature, whether seen streaming behind a dog in full flight or subtly shifting during a turn. While science suggests that its role as a counterbalance may be less dramatic than once believed, the tail’s movement is still an integral part of the sighthound’s athleticism and grace. Perhaps it is the combination of physical function and visual poetry that keeps us so entranced, reminding us that not every marvel of nature can be fully measured or explained.

Photo credit:alekta/iStock