Emily Dickinson was only 32 when she started to become reclusive. Hers was an intensely-lived private world that she felt no one could understand, not her intellectually dull father, not her distant mother, and certainly not Thomas Wentworth Higginson whose opinion Dickinson sought as to whether her poems “breathed.” Higginson’s opinion: “Not for publication.” Good for Dickinson for replying to the leading scholar of the day, ‘I smile when you suggest that I delay “to publish” — that being foreign to my thought, as Firmament to Fin.”

In one of the 70 letters written between the two, Higginson must have asked Dickinson, “Who are your companions?” because her response was poetry itself. “You ask of my companions. Hills, sir, and the sundown, and a dog as large as myself that my father bought me. They are better than human beings, because they know but do not tell.”

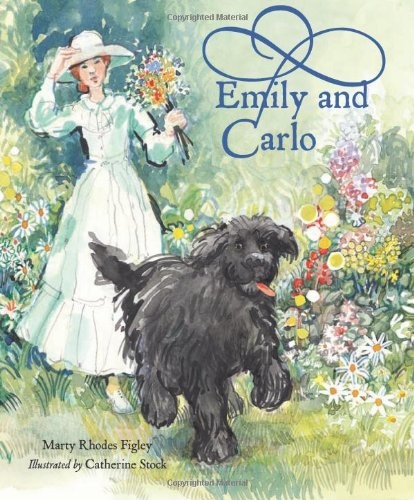

Emily Dickinson was referring to “Carlo,” her brown Newfoundland. The dog (whose company she said she preferred to that of humans’) was a gift from her father who gave his eldest daughter a companion for the long walks she enjoyed in the woods. When Emily made calls, neighbors described how her immense dog stood beside her. One remembered Dickinson saying to her when, as a child, she walked with Emily and Carlo: “Gracie, do you know that I believe that the first to come and greet me when I go to heaven will be this dear, faithful old friend Carlo?”

Carlo died in January 1866 at the age of 17. Months later, Dickinson’s self imposed isolation deepened as she continued to feel his absence. She wrote:

Time is a test of trouble

But not a remedy –

If such it prove, it prove too

There was no malady.

Image of the cover of the book, Emily and Carlo written by