Most standards call for a dog’s withers to be higher than the back (or, put another way, that the rump not be higher than withers). This is because longer spines on the vertebrae of the withers provides better muscle attachment, and that strengthens how the front assembly should work.

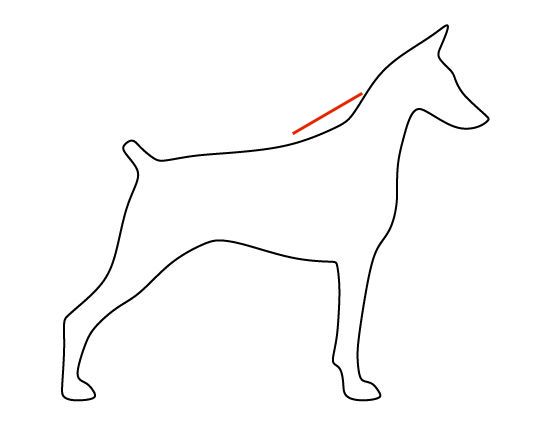

The first line drawing of a Doberman Pinscher shows correct withers as indicated by the straight red line.

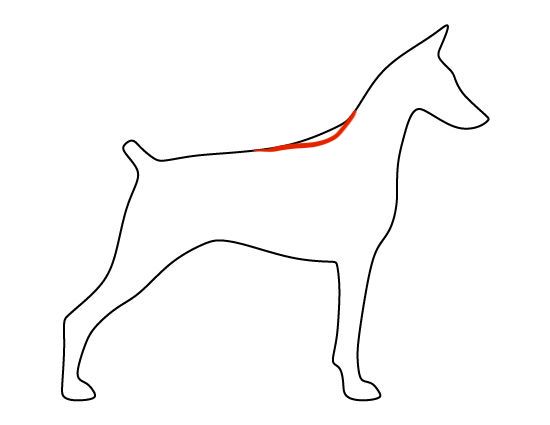

The next line drawing? Not so much. The curved red line shows what the profile of this dog would look like if it had “flat” withers:

“Flat” withers happen when the dog has short vertebral spines instead of long ones. This impacts the length of the muscles attached to them, but flat withers are also the result of shoulder blades being too short which in turn create a wider space between the shoulder blades. Either way, a dog with flat withers has a shorter reach, and in most breeds, this means a limited range of motion and the inability to cover ground efficiently. Flat withers also reduce the ability of the shoulders, elbows, and pasterns to act as shock absorbers; if a dog with flat withers competes in physical performance events (think agility, weight pull, carting, flyball, etc.) that dog is destined for pain since he or she is at higher risk of getting irritated, inflamed, torn or stretched tendons, namely, tendonitis.

Structure matters even in dogs that aren’t competitive in a sporting arena. How many dogs do we know that catch frisbees for fun? It pays to learn about structure even for the “pet owner” (as opposed to a fancier) and if it’s determined that one’s dog has flat withers, what then?

In that event, one continues to love their dog. Spoil her, continue those walks through the woods, but be mindful of her limitations. If playing with a flying disc is an activity someone really enjoys doing with their dog (and thus, it’s important), our suggestion is to get the next dog from a responsible breeder who health tests and is well aware of structure.