When seated at a well appointed breakfast table set with fine linen, elegant platters and golden goblets, the last thing one would expect right after the last course has been served is to be handed a plate of “fumes,” or deer droppings. Among nobles in the Middle Ages, however, that’s exactly what happened. A formal breakfast was served picnic style in the forest before a hunt commenced, and in the course of the meal, the Master of the Hunt was presented with collection of “fewmets” that had been gathered from various locations in the forest. What made a “fewmet” not just a plain old piece of deer poo is that it was the feces of a specific hunted animal, and it provided a good deal of information about the animal that left it.

With an air of expertise (and presumably a bit of drama), the Master of the Hunt examined the droppings, broke them apart,  give them the sniff test, inspected their texture and consistency, and ultimately pronounced the age and sex of the deer – typically a red deer stag – that left each dropping, how strong the animal was, and how recently the scat had been deposited.

give them the sniff test, inspected their texture and consistency, and ultimately pronounced the age and sex of the deer – typically a red deer stag – that left each dropping, how strong the animal was, and how recently the scat had been deposited.

The men then chose the biggest and strongest animal to hunt, typically a deer older than six years old with less than ten points on his rack. The “harbourer” (the local deer expert used by the hunt to gather the fewmets) would show the “lymerer” (the chap in charge of the hounds) where the selected fewmets had been found, and from there, the hunt began in a process called “harbouring” the deer.

In those days, the dogs used in such a hunt were scenthounds called “lymers,” dogs that canine historians believe were Talbot Hounds or St. Hubert Hounds, both breeds that factor into the modern Bloodhound’s ancestry. The hounds were kept on a leash since they were tasked only with finding the deer, not chase or catch it. Once they picked up a hot trail, the lymer’s work was done since the rest of the hunt was communicated via horn. The limer which had “harboured” the deer was rewarded with a special part of the carcass during butchering – often the animal’s head. Yum.

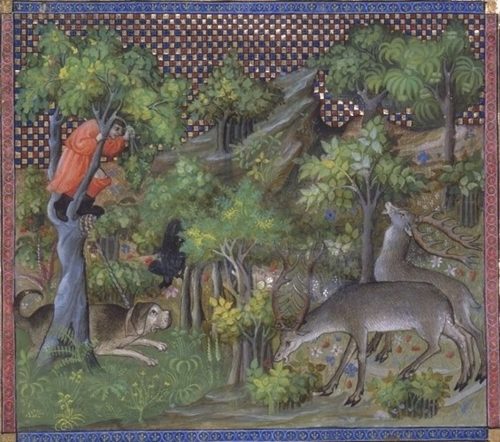

Top image:Finding the Hart from the famous medieval manuscript Livre de la Chasse by Gaston Phoebus, Count de Foix. The handler has tied his heavily built limer to a tree, which he has climbed to spot the deer. Public Domain.

Center image: A limer during a hunt, artist unknown/uncredited – a published image of picture painted in Medieval times and assumed to be in the public domain. Found via wikimedia.