If they worked in a British cotton mill, it was amidst the deafening roar of machinery. Mill equipment had many moving parts, and that made them dangerous: Workers could lose fingers or hands, and one ten year old girl (child labor was common in the 1800s) was crushed to death when her apron strings got caught in a drawing frame and dragged her into a spinning machine. And then there was the air: It was necessarily hot to stop thread from snapping, and it was filled with cotton particles. In the 19th century, there were no N-95 face masks to protect the lungs of workers. Many workers developed mouth cancers, or Byssinosis, a lung disease.

And then there were mines. Coal was used to create iron, heat buildings and power massive steam engines. In the early 19th century, miners could expect to work twelve or more hours a day in almost complete darkness. Roof collapses were common, and explosions always possible. Hundreds of feet under ground, ventilation was poor, and respiratory illnesses were common. Many men died prematurely. Miners who complained or didn’t work fast enough were often beaten.

Grim work, and yet the hard bitten men who supplied the hard labor for mills and mines developed exquisite breeds like the Whippet, Manchester Terrier, Yorkshire Terrier, and Bedlington Terrier, dogs that filled niches in the life of a laborer: The Bedlington hunted vermin in the mines of Bedlington, Northumberland. Yorkshire Terriers were small enough to get at mice and rats nesting under mill equipment; in coal pits, they destroyed the nests of rats, creatures that scurried amidst miners laying on their back as they dug, and often getting bitten.

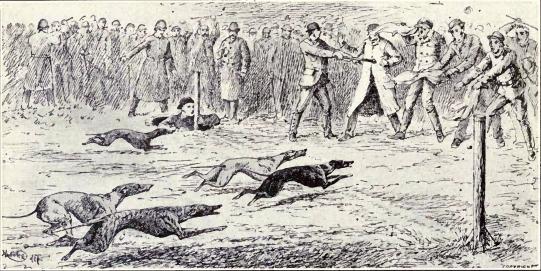

On their days off, coal miners in the north country enjoyed both rabbit hunting and dog racing – enter the Whippet. The breed was created by men best described by Juliette Cunliffe in her book, “Sighthounds:” “Heavy limbed, huge-framed, grimy delvers into the bowels of the earth.” Imagine such men having their calloused and sooty hands in the development of a breed like the Whippet, a canine work of art! Look at this photo!!

Cunliffe quotes another author, Croxton Smith, who presented a succinct description of refined and elegant Whippet when he wrote: The breed has “mastered the secret of annihilating time and space.” Whippets were hugely popular with coal miners in Northern England as a means to earn an extra quid. No fancy equipment was needed for a “rag race,” someone simply waved a rag to trigger the hound’s chasing instinct, and a “slipper” would release or even toss the dog into the race.

Whippet racing never reached the popularity of Greyhound racing, but Whippets were cheaper to keep than a Greyhound, and betting on them provided a little extra income.

A capped mine shaft and winding engine house at Snowden; photo by David Long, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2995811

British coal mines. At well over 3,000 feet down, Snowdown coat field pit was the deepest, hottest and most humid of all them. Regarded as the worst colliery pit in which to work in all of the UK, it was dubbed “Dante’s Inferno” by the miners, many of whom came from South Wales and spoke with nearly indecipherable Welsh accents. One miner could drink 24 pints of water in an 8-hour shift, and there were frequent cases of heat stroke. If ever anyone needed “down time,” it was a Snowdown miner. Since Snowden miners’ housing was built round a central circle, it was used as a Whippet racing track by the residents. As an aside, Snowdown closed in 1987, the shafts capped a year later.

Betteshanger Colliery was the biggest coalfield in Kent, its circular road the length of a dog racing circuit and used by miners to race their Whippets. The first Whippet race was held in the Kent Coalfield on Clarke Field of Ackholt Farm, and reports indicate that around 300 people attend the event described as “very orderly” by the “Dover Express.”

Though the short video at this link is from 1941, it’s a nice bit of history to watch.

Image: Old-time whippet race from 1915 is in the public domain