We struggle with the work of Dr. Samuel A. Corson who spent years using dogs to conduct research on the effects of stress on dogs. He kept the dogs in his laboratory in the university’s psychiatric hospital, and however else we feel about what he was doing, most peers believe that his work ultimately lead to the concept of therapy dogs. In fact, Corson is known as the father of pet-assisted therapy.

It all began with a severely withdrawn teen-age patient-resident of the hospital who heard dogs barking and asked to see them. He was allowed to visit the kennel and take one of the dogs for a walk. The teen-ager, who’d barely spoken to the staff before this, was so enthusiastic and communicated with such animation that his therapist immediately began using the dog in therapy.

Corson and the other hospital psychiatrists were so taken by the boy’s response to the dog that they began systematic experiments using dogs with other patients. In one case, a 19-year-old psychotic patient who’d been unresponsive to traditional treatment and spent most of his time lying on his bed opened up so quickly when a dog was brought to his room, that he was soon released as cured! What family wouldn’t want that for their loved one?

Corson and his colleagues found that pets had been used in psychotherapy as early as the 18th century, and at least one paper was written on the subject in the 1960’s, but it was Corson’s research that was credited with helping to stimulate a surging new interest in the field.

We’re not entirely sure why because it wasn’t a new concept. Child psychologist, Boris Levinson, of Yeshiva University gave the formal presentation of animal assisted therapy before a national audience in North America. He’d been working with a very disturbed child and found, by chance, that when he had his dog “Jingles,” with him, the therapy sessions were far more productive. No matter, it seems. Levinson’s talk was not received well, and many of his colleagues treated his work as a joke.

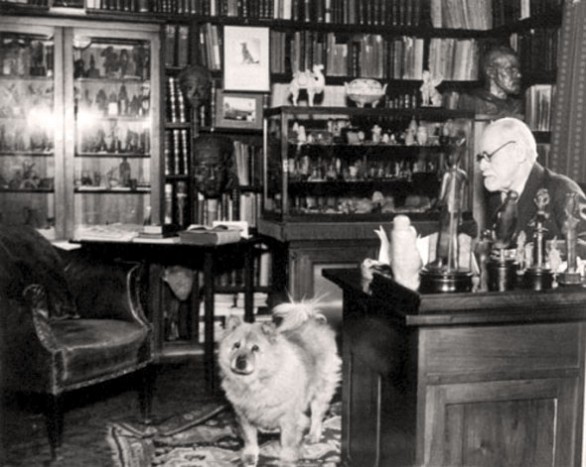

Long before Levinson came Sigmund Freud, the founding father of psychoanalysis. Not as well known is that Freud was a dog person, and in particular, a Chow Chow affectionado (thanks to Princess Maria Bonaparte. Yes, that Bonaparte). Freud pioneered the therapy-dog movement when he had his own dog, “Jofi,” sit in on his psychotherapy sessions because Freud realized that dogs had a calming effect over people. He thought they had an ability to read people’s emotional states and were great judges of character. Jofi would lie near a patient if the patient was calm, whereas she would keep her distance if the patient was anxious.

Frued treasured his dogs’ lack of ambivalence, as well as their devotion, grace, and fidelity. “Dogs love their friends and bite their enemies,” Freud was known to say, “quite unlike people, who are incapable of pure love and always have to mix love and hate in their object-relations.”

Not a news flash to the rest of us who’ve lived with dogs for years.

I am always amazed at the “discovery” we make over the effects that critters, dogs in particular, have on people. Years ago, when we still had psychiatric hospitals, my neighbor worked on the home farm for the state’s psych hospitals. They had their own dairy herd etc. He has great stories to tell of the patients that would work with them and what a beneficial effect the critters had on the patients. Such stories have been in place right before us, and we have failed to see them.

You are so right, Linda. We’ve come across many accounts similar to yours!