We like foxes! We wish these curious and mischievous creature no harm, and consider it a special moment to spot one in the wild. We understand, too, however, that back in the day, these sentiments weren’t shared by British farmers, landholders or stockmen because foxes often caused extensive property damage when scavenging for food, and posed a significant threat to poultry and rabbit farmers, and sheepmen. Foxes were widely regarded as vermin and were hunted as a form of pest control.

In the eighteenth century, fox hunting morphed from necessity to sport, in part as a result of the decline in the UK’s deer population. The Inclosure (Consolidation) Act of 1801 nudged the sport into the 19th century, and modern fox hunting took shape under Hugo Meynell who turned the hunt into an exhilarating chase by using faster Northern hounds. Indeed, Meynell considered horses merely as vehicles to the hounds, and advanced hound and horse breeding techniques which revolutionized the exercise.

Fox hunting endured until 2005 when the UK’s Hunting Act made “hunting wild mammals with a pack of dogs (three or more used in the traditional style) unlawful in England and Wales. Our post, however, focuses on a couple of hound packs that were used and shaped by the sport.

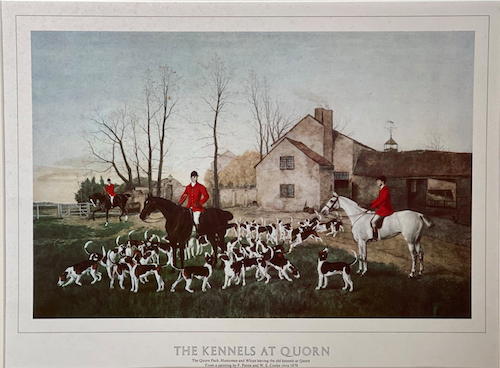

England’s oldest fox hunt – the Bilsdale Hunt in Yorkshire – was established by George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham in 1668, and it’s still running today. The first pack to concentrate its attention on foxes, however, was the Quorn Pack formed in 1698 by Thomas Boothby. He hunted the pack for an astounding 55 seasons until 1753 when Hugo Meynell (the very same) took over the mastership until 1800. Finding the pack too slow inspired him to evolve a hound that was fast, compact, well nosed, full of samina, and capable of “sticking to a line.”

In 1806, small hounds were favored, the largest dog in the Quom pack was under 23 inches; but when Assheton Smith took over the mastership, he found that that the small hounds couldn’t jump over fences that were too thick to creep through, and he soon raised the standard of the hounds to 25 inches in height, and of bitches to 23. He subsequently lowered the standard to suit the country, however.

The Quorn Hunt is still in existence, and continues to go out on rides four days of the week during autumn and winter months. Between 100 and 150 mounted people are involved, and twice as many who follow the foxhounds on foot, in cars or on bicycles. Not every hunt, however, goes as planned, and mourners at a woodland funeral in 2019 were horrified when a fox chased by dogs from the Quorn Hunt bolted into proceedings at the Prestwold Natural Burial Ground, near Loughborough and reportedly leapt over an open grave.

But we digress.

Twelve to fifteen couple is the ideal number of hounds for the Quorn, and while back in the day a dog pack and a bitch pack were used, more often these days, they’re mixed as there are not quite the numbers of hounds being bred as there once was. There is still a Puppy Show, though harder to ascertain is the breed of the hounds being used beyond a strong French influence.

We came across a video shot just a few months ago that you may find of interest:

A

A character in Oscar Wilde’s play, A Woman of No Importance called fox hunting, “the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable.” Fox hunting endures, if only to pursue scent, and not an actual fox, and no less so in the United States. Interestingly, an article by David Walter published in 2018 asks: Will a new generation of fox hunters save their controversial sport? He cites a statistic that points out that in America, the number of fox hunters — some 20,000 riders nationwide — has not changed in a century, even as America’s population has increased dramatically, and goes on to explore the morality, and future, of the endeavor. It’s worth a read. You may also find this piece about the current Huntsman of the Quorn, Peter Collins, of interest.