It sounds like the opening of a joke: Why did the cow climb the mountain? Sorry, the answer isn’t funny because it’s not a joke question, although we suppose we could wing it. Try this: A cow’s son made a model of mount Everest for his school project (work with us, here). The dad cow asks his boy, “Is it to scale?” The young calf responds, “Don’t be stupid Dad, it’s just to look at!”

Badad boom.

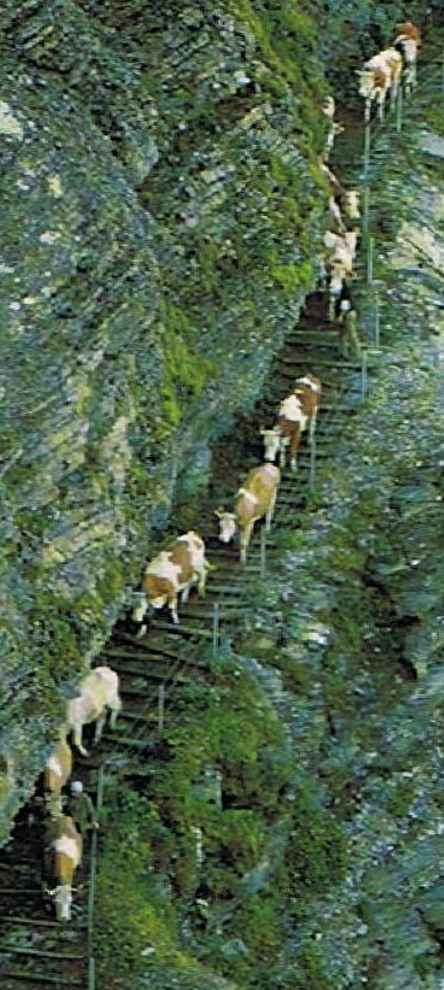

This image comes from the National Entlebucher Mountain Dog Association AKC Parent Club

In all seriousness, cows have always climbed mountains in Switzerland, and if you were a Swiss dairy cow, your greatest danger came not from predators, but from navigating the terrain of the Alps. Trails are narrow, often steep and serpentine, and yes, dangerous. And yet according to the country’s Federal Office for Agriculture, some 270,000 cows are marched from their valley farms to mountain meadows at the start of every summer, and back down again in early autumn. On average, a Swiss cow can climb about 1,936 ft over ten miles, and it can be a hard climb.

We should mention that this isn’t a case of a Swiss cow feeling mooved (couldn’t resist) to pull on lederhosen and run through meadows singing, “The hills are alive with the sound of music…” Cows climb the Alps because that’s where the food is, but mostly because that’s where dairy farmers make them go. There is incentive to herd cattle high. Top dollar comes with aromatic Alpine cheese produced by cows that munch on tasty alpine grasses and herbs, and these days, it’s known that cheese produced by the milk of these cows is particularly high in omega-3 fatty acids, and much preferred by health conscious customers. The government also rewards farmers who take their cattle up the mountains with subsidies worth hundreds of dollars per cow each summer. Finally, and if you can believe it, there is tourist dollars to be had. Professionals, from doctors and lawyers to architects and teachers, are among those who sign up for “skill vacations” to learn how to herd and make cheese.

Raising cattle became the dominant form of agriculture in the Alps as early as the 14th century, and since that time, it’s been known how helpful a dog is. Enter the “dog of the Alpine herdsman,” better known to us as the Entlebucher Mountain Dog, a drover specialist from the Entlebuch region in the Canton of Lucerne, Switzerland. The Entlebuch region is just 22 square miles in size, and throughout the breed’s history, the Entlebucher has worked in this and other mountainous areas of Switzerland. This smallest of the four Swiss Mountain breed was tasked with moving cows up the mountain, and then back down again after they were finished grazing, and as we pointed out earlier, cow trails were narrow to the point of being single-file only. Entlebuchers drove the herd with their shoulders to a certain point on the mountain, then helped keep the cows safe and on the proper paths. It took a mentally and physically sound dog to do this work.

Since 2003, an alpine cattle descent has been celebrated in September in the UNESCO Biosphere Entlebuch, a reserve that covers some 39,000 hectares (150.58 square miles) and reaches an altitude of 1.46 miles above sea level. Several alpine families wearing native garb walk with over 200 cows and oxen from the authentic alpine huts around Sörenberg down to Schüpfheim. The high point of the decent is a magnificent parade through the village, and yodeling and alpine horns serve as the auditory backdrop. A large market offers alpine cheese, sausages and jam, and local pubs decorated by local associations are “jammed” with visitors. The alpine cattle descent is a wonderful celebration of customs and traditions, and you’ll want to go after seeing the video below:

Get more information about the descent here.

Image:by © Katho Menden/Dreamstime.com

the original was as you listed first — that’s where the food is. Cattle (and sheep) both are marched up and down mountains because the amount of food available in a valley is limited — and so is that on a mountain. in very mountainous terrain (as in Switzerland), if one did NOT go up and down the mountains regularly, there’d be precious little graze available for the cattle. In other areas (parts of France and the US as well as elsewhere), the graze is seasonal. Down in the valleys for the winter, up into the mountains for spring and summer.) Transmontane tending is well known, at least historically, in France, Spain and again, in the US.