We confess a fondness for collective nouns – words that refer to a group or collection of people, animals, or things. The collective noun for a group of sheep, for example, is a flock, though some people refer to them as a herd. Technically speaking, the term “herd” is used for terrestrial animals gathered together in a group, while “flock” refers to a group of birds, especially a group gathered to migrate. To get even more precise, a group of sheep can also be called a “mob,” but when a group of sheep number up to a thousand animals, then it’s known as a “band.”

But we digress.

We like collective nouns because many of them seem nonsensical. A murder of crows? A bike of bees? A rhumba of rattlesnakes? And how about people? It’s a flight of dancers, a glitter of generals (due, we’ve read, to the metal stars that signify their elevated rank), panel of experts (evolved from pannellus, the Latin word for a piece of cloth once used to describe pieces of parchment on which jury lists were written), and our new personal favorite, a superfluity of nuns.

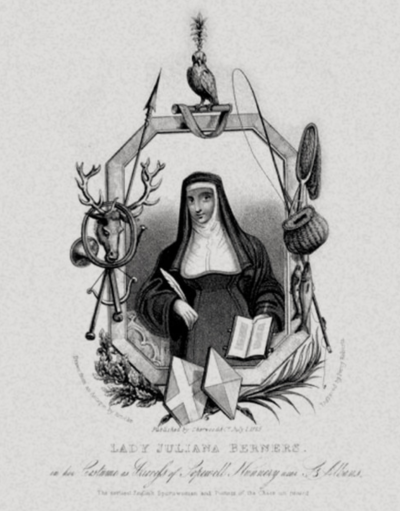

As a rule, ‘superfluity’ refers to an excess of something, so we got curious as to why the word was applied to religious sisters. We read of one possible explanation: Between 1270 and 1536, England nunneries were overcrowded, all one hundred and thirty-eight of them. Hardly the result of religious fervor, the convents were packed because noble families whose daughters who had passed a “marriageable age” admitted them to nunneries. Though the nunneries were already burgeoning, Superiors, or prioresses, were forced to accept the daughters because of pressure from the lords. Unmarried women had few options in those days. Enter religious service, or spin for a living (hence ‘spinster’). It’s possible that Dame Juliana Berners, the prioress of Sopwell Priory near St Albans, was one of these Mother Superiors. We mention the good lady, however, for another reason.

In 1486 (dates vary), the St Albans Press in England printed the Book of St. Albans, a three-part compendium on aristocratic pursuits, namely hawking, hunting, and heraldry. The essay on hunting is attributed to Dame Berners who, even as a nun, retained her love of fishing and hunting. Indeed, many women’s fly-fishing clubs and associations in the United States and Europe are named for Berners in tribute to her legacy as the first author of either gender to chronicle the fine points of the sport of angling. It was also in her essay that 160 collective nouns for animals appeared (as well as the term, “superfluity of nuns”). They included a gaggle of geese, a blast of hunters, and a melody of harpers.

The Book of St. Albans also listed the names of “diverse manner of hounds,” or dogs that were known as the time. They included the Greyhound, “bastard” (a Greyhound cross), “mongrel,” “mastiff,” “lymer,” “spaniel,” “rache” (a running hound), “kenet” (a small hunting hound), “terrier,” “butcher’s hound,” “midden-dog,” “trundle-tail,” “prick-eared cur,” and small ladies’ puppies to bear away fleas.

Greyhound owners may be interested to know how a good example of their breed was described at the time:

A Greyhound should be headed like a snake

And necked like a drake,

Footed like a cat

Tail like a rat

Backed like a Beam,

Sided like a Bream

Some believe this to be the first written description of any breed, and it was said to be written by (wait for it)…….Dame Juliana Berners.

In her novel “The Ninth Hour,” “author Alice McDermott writes, “It’s the nuns who keep things running,” Given Dame Berners’ impact on language and some of what we know about dogs in the Middle Ages, it would seem that one nun, at least, also got things started.

That said, it should be mentioned that not everyone believes Sister Berners existed at all, and to read more on that, visit here and here.

I LOVE these deep histories! History teacher encyclopedia-of-dogs loving fan here!