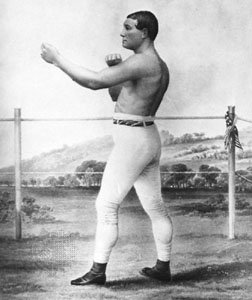

He stood at just 5 feet and 8 inches tall, and never weighed much over 150 pounds. He was poor and he was illiterate, but the former  bricklayer became the world’s first heavyweight boxing champion in 1860. In fact, his final contest with an American champion fighter is widely considered to be boxing’s first world championship. Certainly, it was the bout that made him a national hero in Great Britain. In fact, chances are good that when you see a vintage image of a Victorian boxer, it’s Tom Sayers.

bricklayer became the world’s first heavyweight boxing champion in 1860. In fact, his final contest with an American champion fighter is widely considered to be boxing’s first world championship. Certainly, it was the bout that made him a national hero in Great Britain. In fact, chances are good that when you see a vintage image of a Victorian boxer, it’s Tom Sayers.

His ability surfaced when as a bricklayer working on Wandsworth Prison, he was struck by a supervisor described as a “great big bully of a fellow.” When Sayers returned the blow, the fisticuffs were moved to a nearby common. After an epic fight, Sayers knocked the supervisor out cold, and an underground career as a bare-knuckle fighter was launched.

Boxing at the time was “raw.” There were no formal weight divisions, no round limits, and Queensberry rules wouldn’t be published for another 18 years. Fights could go on for hours, a bloody spectacle of endurance. In a 16-bout career lasting a decade, Sayers lost only once, but it was his last appearance in a ring when he fought John Heenen, a younger, taller, and heavier opponent by nearly 50 pounds that people remembered. Early in the fight, Sayers broke a bone in his right arm, but his bare-knuckled left fist still left Heenan’s face unrecognizable. After forty-two rounds lasting two hours and 20 minutes, spectators stormed the ring and the fight was declared a draw. Both men were awarded a championship belt, but Sayers’ position in boxing folklore was fixed.

History doesn’t reveal how a Mastiff named “Lion” came into Sayers’ life, but by early 1861, mentions of the dog showed up in the press. The Sporting Life newspaper reported that same year that Sayers was seen near London’s Haymarket “accompanied by a noble mastiff dog which looks as formidable as his master has proved himself to be in the pugilistic arena.” Months later, the Falkirk Herald wrote that the fighter was seen with “a huge, brown-coloured English mastiff called ‘Lion’ which appears to be much attached to his master.” As close as the pair appeared to be, Sayers nearly lost the dog to financial burdens. He had become the owner of a large equestrian circus, but a year later, the former champ decided to sell off the entire circus including all the horses, the “celebrated performing mules, “Pete” and “Barney,” and Lion.

When Lion came up for auction, bids were furious, but Sayers had a change of heart and ordered his secretary to buy the dog. The mastiff was secured for 21 guineas. Over the next couple of years, Sayers and Lion were a familiar sight in London, but by that point, Sayers suffered from diabetes and Tuberculosis both made worse by a drinking problem. On November 8, 1865, Dayers died at the age of 39 in the presence of his father and two children.

The funeral that took place a week later was the largest in the history of Highgate Cemetery, such was the public’s affection for “The  Little Wonder,” and “The Napoleon of the Prize Ring.” Over 10,000 people followed his coffin to its final resting place in North London’s Highgate cemetery; Lion sat at the front of the cortege with a crepe ruff around his neck as the coffin was carried to Highgate, he, the “chief mourner.”

Little Wonder,” and “The Napoleon of the Prize Ring.” Over 10,000 people followed his coffin to its final resting place in North London’s Highgate cemetery; Lion sat at the front of the cortege with a crepe ruff around his neck as the coffin was carried to Highgate, he, the “chief mourner.”

After his master’s death, Lion was up for auction again, and this time he was purchase by a close friend of Sayers. Later, townspeople had a statue made of Lion to lay next to Sayers for eternity which was installed over the grave in 1866. Lion, however, was sold yet again, and at this point, all that’s written is that he later died on a country estate.

Sayers was inducted into the Ring Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954, and into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990