In 1994, dogs were banned from Antarctica.

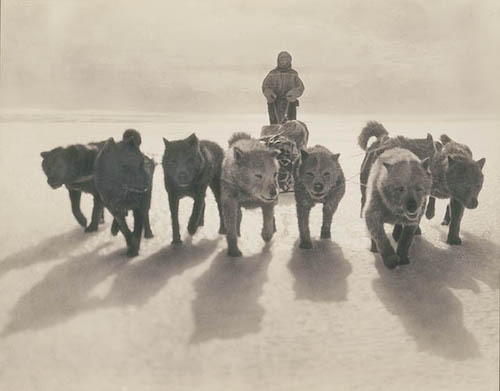

It was a startling event when the land that huskies arguably “owned” no longer allowed them, though for understandable reasons. Huskies were a big reason that Roald Amundsen became the first person to reach the South Pole in 1911. Less successfully, Robert Scott used sled dogs in Antarctica (he and his four companions died on the return journey), but the story of Antarctic exploration cannot exclude mention of the Huskies that pulled sledges, fed men (or each other), and provided companionship (though they were not thought of as pets).

Because of an environmental clause in the Antarctic Treaty in 1993, dogs had to be removed from Antarctica by April 1994. The ban was introduced because of concern that dogs might introduce diseases such as canine distemper that could be transferred to seals, or that they might attack wildlife. As an aside, it was also thought to be inconsistent for the Protocol to have strict controls on the introduction of non-native species but still allow huskies to be bred and used in Antarctica.

A small number of dogs had been kept at Rothera Research Station in the 80s and 90s, in some measure to give researchers a feel for what it was like to have been an earlier explorer or scientist. They were also good for morale in an inhospitable environment, so there was considerable push back from people at the station when the legislation for the removal of the dogs was put in place.

The dogs spent their last season doing what huskies do: Pulling a sledge in support of a surveying project on Alexander Island. When the fourteen remaining dogs were removed from Rothera in February, 1994, special kennels were built and fitted inside a BAS Dash 7 aircraft for the 5-hour flight to the Falkland Islands. The Huskies spent several weeks acclimating to a warmer climate and experiencing grass, sheep and even kids for the first time. From the Falklands, they flew to the UK on a special RAF Tristar flight and were treated to a warm welcome on British soil where they began a period of quarantine. The dogs actually became media stars in all the national papers.

Once quarantine was completed, the final leg of their journey took them to Quebec in Canada, courtesy of British Airways. Sadly, five of the dogs died the first year because of illness, nor was it possible to breed any of the remaining dogs. The last two Huskies died in 2001.

For clarification, the name “husky” is often used to describe a number of breeds of northern-hemisphere snow dogs, but it was Amundsen who recruited Seppala to train a group of Siberian Huskies for an expedition to the North Pole.

Anyone interested in this fascination story may want to read “Of Dogs and Men: Fifty Years in the Antarctic” Edited by Kevin Walton and Rick Atkinson (1996).

Image of the first Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-1914)

I have been to Antarctica and the man whose job it was to take these dogs away was on our boat and he said they were given to the Inuits, who didn’t feed them and that is why they died.

We sure hope the man you encountered on the boat was wrong, Elizabeth. What a very sad end for dogs that deserved better.