Sixteenth century French hunters weren’t fools. They knew they had a good thing in the Basset Hound when it came time to put food on the table, and for the most part, they knew why. The breed’s short-legs made it easier to follow the dogs on foot, the only option available to the average person because until after the French Revolution, hunting on horseback was the preserve of kings, aristocracy, and gentleman squires.

The same short legs enabled the dogs to keep their noses to the ground without having to crane their necks, and this meant they didn’t tire as quickly while running. These hunters also knew that Bassets were excellent “sniffers,” though they had no way of knowing why. Many modern day cynologists place the Basset second only to the Bloodhound for a huge number smell receptors (over 220 million, for anyone counting); the portion of their brains responsible for the sense of smell is 40 times that of a human who has just five million scent receptors!

What the breed wasn’t known for was running, at least, not the way a longer legged hound runs. It doesn’t mean it can’t. Check out 8 minutes of highlights from the 2008 AHBA World Hunt (American Hunting Basset Association) in which no animals were harmed, but rather, a Basset Hound’s skills at tracking/trailing a rabbit’s scent are tested:

As you saw, Bassetts haven’t lost a step from the time they were tasked with scaring rabbits and hare out of brush so that hunters could swoop in and nab that night’s dinner, but did you know that Bassets were also used to flush out horses?

The question is asked tongue-in-cheek as a segue to introducing “George.”

When Toby Wilt arrived at Vanderbilt University to play freshman football in 1961, he brought along his affable Basset Hound, “George.” They lived at the Sigma Chi House, and at football games and practices, George would be in attendance, courtesy of Wilt’s girlfriend.

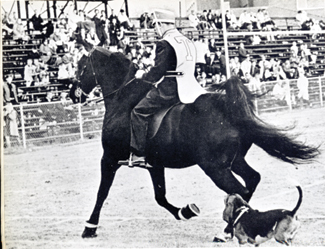

Wilt was probably a junior when Vanderbilt played Tennessee on November 28, 1964, and as usual, George was there. At some point during the game, George took issue with the University of Tennessee’s mascot, “Ebony Masterpiece,” a Tennessee Walking horse. George shot off across Dudley Field and ran the startled horse right out of the stadium to the delight of Commodore fans. With Wilt’s 40-yard run from his halfback position, he set the team up for the winning score. Later, Wilt said, “I don’t really know what George was thinking. My guess is that he had never seen a horse before and thought it was a big dog.”

Today, we would be horrified at the risk posed to both dog and horse, but at the time, Vanderbilt football fans were tickled. Following George’s assertion that only one four-legged animal had field privileges, and it wasn’t the horse, George became the most revered animal on campus, loved (and fed) by all. He became a VIP of the athletic department, and at least half a dozen photos were devoted to him in the 1965 Commodore yearbook.

Not everyone loved George. In the spring of 1965, the Metropolitan Health Department disapproved of a dog living in a fraternity house and “officially” expelled George. The school’s Council of Student Activities voted to build a house for George, its estimated cost of $2,000 raising eyebrows (well, the house did include carpeting, and central heat and air condition). In the end, a regular doghouse was donated for George.

Speaking of “ends,” George met his a year later when he chased an ice truck on the Vanderbilt campus and was killed. Bereaved students buried him in a donated casket in a small plot just North of Dudley Field. Though another Basset Hound, “Samantha,” would fill George’s place, the idea of a Basset hound mascot was abandoned after Samantha’s owner graduated in 1970.

Image of running Basset Hound found on Pinterest and happily credited upon receipt of information