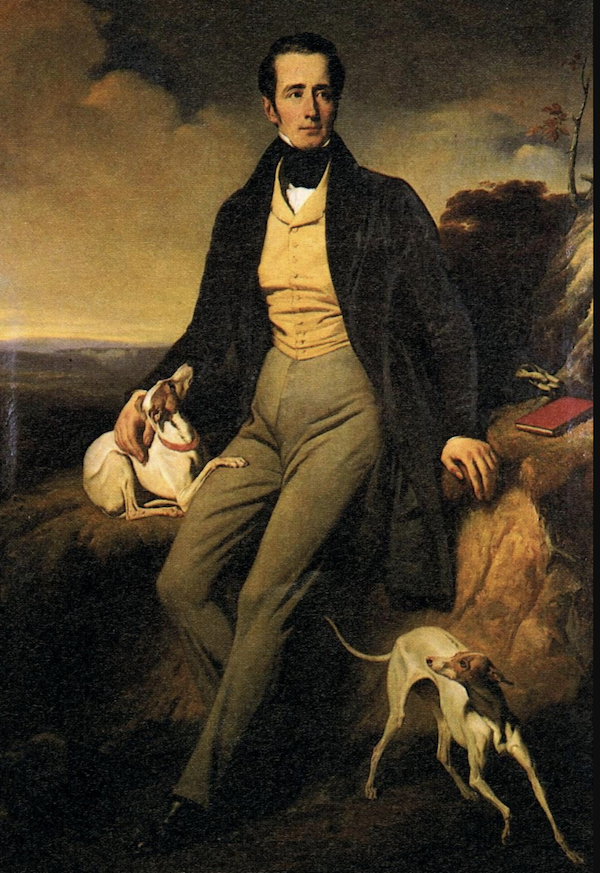

Portrait of Alphonse de Lamartine by Henri de Caisne

Biographies of Alphonse de Lamartine write that he was one of the greatest French poets of the nineteenth century, a pioneer of the French Romantic movement whose poetry marked the transition from the stuffiness of the neoclassical era to the passion and lyricism of the Romantics. He was all that, but he also became a statesman who rose to considerable political prominence in early 1848. Indeed, de Lamartine briefly led the Second Republic, the state that had been established after the Revolution of 1848 (the first French republic had been formed during the French Revolution.) Because of him, France kept the Tricolore as its flag.

He was also a historian. In 1833, de Lamartine observed how the city of Istanbul cared for its canine population:

“The Turks themselves live in peace with all the animate and inanimate creation—trees, birds, or dogs; they respect everything that God has made. They extend their humanity to those inferior animals, which are neglected or persecuted among us. In all the streets there are, at certain distances, vessels filled with water for the dogs.”

Sadly, this didn’t last. The Hayirsizada Dog Massacre was a cruel response to modernization where dogs came to be associated with poverty and a lack of sanitation, but de Lamartine’s early commentary revealed the man as someone who took note of dogs, and not ignored them.

You have probably come across the following quote many times and thought that it is attributed to Mark Twain: “The more I see of the representatives of the people, the more I admire my dogs.” Some sources, in fact, claim that Lamartine said it first. It’s possible that the expression may already have been in circulation by the time de Lamartine wrote it, but if nothing else, he helped to popularize it. De Lamartine also wrote, ““When a dog is in your life, there is always a reason to laugh,” and, “My dog! the difference between thee and me knows only our Creator.”

De Lamartine was an Italian Greyhound affectionado and breeder. He easily accepted offers to pose with his favorite dogs for paintings, and devoted beautiful verses to them. He was also keenly aware of their need for a light touch when it came to treating them if ill. In a letter to a friend to whom he was giving a pup, he wrote, “If he coughs, give him little mallow. Nothing else. The doctors kill them all because these are not dogs, but four-legged birds.”

Just when we thought we were finished with this post, we stumbled upon the full note, and we share it because people don’t write like this anymore. Breeders, however, will be able to relate:

“M. de Lamartine has the honour of sending to Mme. la Comtesse de Boigne the friend which she has desired, which he has reared for her and which he can recommend with feelings entirely paternal. It is the most sensitive and intelligent animal that he has ever known, and he feels more grief at separation from it than he can venture to admit.

“It is not yet entirely trained, and requires patience for some time longer. A gentle word of reproach is the only punishment needed for this kind of dog; to do more is to destroy for ever the freshness of its character.

“It has had the distemper, but should it cough, a little mallow water is all that is required, never anything more. Veterinary surgeons kill dogs invariably, because they forget that these are not dogs, but four-footed birds.

“The first few days the dog will be rather downcast, and it will be better to have another dog to keep it company. It is fed on bread, with vegetables and a little chicken, but no other meat.

“I must ask pardon for all these details, but in six months Mme. de Boigne will understand their necessity, and I ask her to accept, together with this information, my kindest regards.

“ A teaspoonful of olive oil with sugared mallow water, or the water mixed with honey to drink ; vegetables, spinach, etc., to be eaten with bread only twice a day; this is the medicine and the diet. It should be taken out in the garden for a little, and should eat dog’s grass.

“I greatly regret that I have not been able to avail myself of the kind permission of Mme. la Comtesse de Boigne to call, but from eight o’clock in the morning until midnight there is not an hour’s time for pleasure when one is so doubly occupied as to be both deputy and poet.

“With kindest regards,

Lamartine”

The passage was found in the Memoirs of the Comtesse de Boigne 1781-1830 (published in 1907).