The oldest continuously published sporting dog journal in the United States is The American Field which dates back to February 1874. It’s probably the oldest because it’s associated with the oldest purebred dog registry in the US, The American Field Sporting Dog Association founded in 1874. The AKC was established ten years later in 1884, and based on hunting dog registration, the United Club registry came even later – 1898 – with over 60 percent of its 16,000 licensed events each year dedicated to hunting ability, training and instinct tests.

Most registries work only with breed bloodline purity, and when we see that a stud book (an official list of dogs known to be purebred members of a breed, and whose parents are known) is “closed,” it means that registered dogs must be from a registered set of ancestors, and that all subsequent offspring trace back to the foundation stock. The AKC, for example, allows new breeds to develop under its FSS (Foundation Stock Service), and for the breed to move to the Miscellaneous class and onto full recognition, the breed’s stud book must be closed.

Conversely, an “open” stud book allows some outcrossing, usually in service dogs like police or herding animals. The AKC has occasionally gotten requests to open or to close a stud book for reasons that range from accepting dogs with pedigrees outside the AKC, addressing gene pool diversity, having too few dogs registered with the AKC, or health considerations, and it has guidelines regarding such requests.

The concept of dog registries dates back over 100 years, and today, here are many such registries (thirty, by our reckoning), some you may or may not have ever heard of: The United Canine Association, the Continental Kennel Club, the American Canine Association, the Dog Registry of America, America’s Pet Registry, the North American Purebred Registry, and more. There are also single breed registries such as ASCA (the Australian Shepherd Club of America),

You have to be careful with registries. For starters, a registry – any registry – doesn’t guarantee that a dog is sound, of show quality, or even that it meets its breed standard. A registry simply keeps track of a dog’s family tree and offers services. Some registries, however, have been created simply to accommodate dogs bred by breeders with questionable practices, or to cater to a special interest group, such as a commercial breeder’s association, or a pet store chain. A few registries allow an owner or “breeder” to register their dog as a “designer breed,” and AMBOR (American Mixed Breed Obedience Registry), doesn’t register dogs for breeding purposes, but only to record trial results and titles.

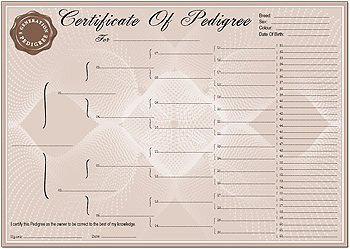

Some registries will accept pictures instead of a pedigree, and people who don’t know any better might be duped dazzled by a fancy looking piece of paper with a three generation pedigree. Yes, Virginia, there are junk registries, and buying a dog registered by such a registry may actually support unethical breeding practices by working with breeders suspended from other registries, or by registering dogs that other registries won’t accept.

It’s not enough to do one’s homework when determining the right fit of breed, and finding an ethical heritage breeder. One must also be careful with registries!