The image you see here caught our attention because it was posted on National Purebred Dog Day by a coin company on Twitter.

When a non-dog entity uses May 1 to promote their business, it suggests to us that NPDD is worming its way into the culture, and this is particularly gratifying because we are reaching a segment of society that we might not reach any other way. In this case, National Purebred Day Day was exposed to coin collectors, many of who may own purebred dogs.

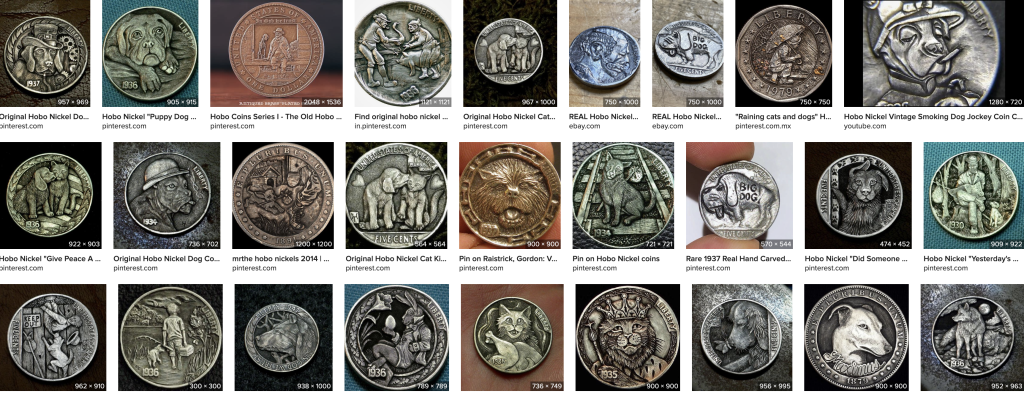

That said, we didn’t know what the dog images on coins meant, and his is how we came to learn about “hobo coins.”

Hobo coins are typically nickels (actual U.S. coins, and usually Buffalo nickels) in which the original image has been carved away and replaced with something more whimsical. The coins are considered to be folk-art, and while it is a shame to carve into an authentic Buffalo nickel with a readable date (such a nickel is worth well above face value, and highly collectible), there is also a market for hobo coins.

The art form got its name because hobos and itinerants started carving them on long train rides during the Depression, but in actuality, hobo nickels started showing up the year the Buffalo nickel was released – 1931. Nickels were chosen over any other coin because it was cheaper than a quarter, bigger than a dime, and was the right thickness, width, and softness to withstand carving by a nail or the point of a pen knife. Little by little, metal was shaved away to create a miniature bas relief sculpture. In early versions, the Indian chief on one side of the coin would be modified into a bearded man wearing a hat, or even into the likeness of someone famous (during World War I, hobo nickels made fun of the face of Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm). Other frequent themes were skulls, clowns, rabbis, soldiers, and even women. Sometimes, the reverse side of the coin was carved, and those themes included a box car, turtle, donkey and more.

The 1940s, 1950s, 1960s and 1970s were a transitional period for hobo coins. The Buffalo nickel was gradually replaced by the Jefferson nickel, and subject matters became more ethnically and socially diverse. Things really changed in the early 1980s because of the publication of a series of articles by the numismatist, Del Romines, who wrote on the subject of hobo nickels. Some believe this book was the dividing line between “old” hobo coins to “modern” ones.

Today, the art form is still quite alive. Artists now use specialized power tools that make nickels look even more like tiny sculptures. Some artists inlay gold into their nickels, and some actually sign and number their coins much in the way that a run of serigraphs is numbered. The Whippet seen at the top and to the side is one example of the range of images, and by no means is the subject matter limited to one breed as you can see above in the screen shot we took of a search on “hobo coin dogs.”

For anyone wondering, defacing currency in circulation is still illegal, but Hobo coins are legal because they aren’t made to defraud. They are typically traded or sold as artwork, and worth a lot more than five cents to collectors. As for the old hobo coins, some have fetched as much as $24,000 in auctions and trades.

There’s an organization devoted to the subject, the Original Hobo Nickel Society, with more information on their website, www.hobonickels.org.