We think of mascots as something that only high schools, colleges, and a few businesses have, but not “stuffy” financial institutions. In fact, at least 25 banks and credit unions have created mascots to promote their various services, and some of the mascots, such as the ones for Chase Bank, County Bank, and Wells Fargo, are dogs. Sometimes, mascots can become spokespeople for the organization, but sometimes, they are more than that.

Back in the gold rush days, some Wells Fargo agents had dogs to help guard Wells Fargo deposits, and themselves. In 1852, Wells Fargo put 20 year old John Quincy Jackson in charge of a large express office and banking house in Auburn, California. In a letter he wrote to his brother, Jackson said, “What I have to do is quite confining, staying in my office all day till ten at night—buying dust, forwarding and receiving packages of every kind, from and to everywhere [and] filling out drafts for the Eastern Mails in all sorts of sums, from $50 to $1,000.”

Every month, Jackson sent down to San Francisco some $200,000 worth of gold dust, weighing perhaps 750 pounds. Shipments were “frequently 100 to 150 pounds, about as much as one likes to shoulder to and from the stages,” he observed. Was he worried about security? Not at all. “As a friend. counselor, and safe guard,” Jackson owned a devoted 128 pound Mastiff as “friend, counselor and safe guard.”

In Iowa Hill, Wells Fargo agent, T.S. Hotchkiss, helped secure his office with a large, powerful dog named, “Tiger.” “Tig,” as most townspeople knew him, was trained to guard the office safe, which he faithfully did for several years until he died in a fire that completely destroyed the Wells Fargo office.

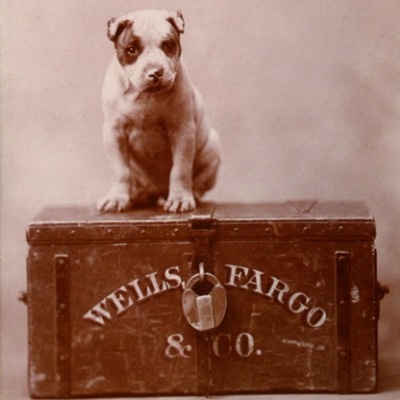

On a happier note, when a Wells Fargo employee placed his puppy, identified as a Bull Terrier, on top of a Wells Fargo treasure box at the Midwinter Fair in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park in 1893, the dog named “Jack” not only became a part of Wells Fargo history, but a universal symbol of security and service for the express business.