In his own way for his time, William Eppes Cormack was a bit of a scientific renaissance man. Born to a Scottish merchant in the town of St. John’s in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, William’s family returned to Scotland in 1805 where William would go on to study at the Universities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. There, a serious interest in botany, geology, mineralogy, and agriculture emerged. At the age of 22, and with the restless nature of youth, William lead a group of Scottish immigrants to Prince Edward Island, but that same antsy energy compelled him to return to St John’s where his family still had business and property interests.

It didn’t take long for the grass to tickle the bottom of William’s feet, so to speak, and within a few months, he decided to take on a task never attempted before by a European, and that was to explore the interior of Newfoundland. Though there had been three centuries of English presence in Newfoundland, settlements were largely confined to the coast, and the interior of the island was virtually unknown. William had three goals in taking on this challenge: He wanted to satisfy his curiosity about the interior, he wanted to advance colonization by opening up the area, and he wanted to make friendly contact with Beothuks, or the“Red Indians.”

With the help of Joseph Sylvester, a young Micmac hunter from Bay d’Espoir, the pair sailed from St John’s to Bonaventure, hacked their way through the heat of thick growth infested with flies, crossed over savannas, around lakes and over rivers, and walked 20 to 30 miles every day westward. Cormack was an admirable witness of what he saw, and he wrote in detail about the weather, the soil, and the flora and fauna. His notes were subsequently published in Narrative, an undisputed classic of Newfoundland travel. Though he failed to meet any Beothuk, his expedition is now seen as one of the most important in the exploration history of Newfoundland.

As students of dog breeds, we are particularly interested in a description that William wrote in 1822 about the St. John’s Water Dog. He noted: “The dogs are admirably trained as retrievers in fowling, and are otherwise useful…The smooth or short haired dog is preferred because in frosty weather the long haired kind become encumbered with ice on coming out of the water.”

His account of two different coat types offers a tantalizing hint that two of our most beloved breeds had already begun to split off from the St. John’s Water Dog: The longer coated type that would become the Newfoundland, and the early version of the short coated Labrador Retriever. The size difference hadn’t yet become apparent, but as the John’s Water Dog is an ancestor of both breeds, cynologists are suspicious that both William’s description and its timing is relevant.

Eleven years later, one Colonel Hawker published, “Advice to Young Sportsmen” in which he made early references to the Labrador Retriever. He used the terms, “Newfoundland,” and “St John’s dog,” interchangeably, but he described a dog that the shooting man should acquire as “by far the best for any kind of shooting, oftener black than any other colour, and scarcely bigger than a pointer. He is made rather long in the head and nose, pretty deep in the chest; very fine in the legs; has short or smooth hair; does not carry his tail so much curled and is extremely quick and active in running, swimming, or fighting.”

Hawker had been hobnobbing with the aristocracy when these new dogs were becoming popular. In his description, he added “Their sense of smell is hardly to be credited. Their discrimination of scent, in following wounded pheasant through a whole covert full of game, or a pinioned wildfowl through a furze break, or warren of rabbits, appears almost impossible.

“A water-dog should not be allowed to jump out of a boat, unless ordered so to do, as it is not always required; and, therefore, needless that he should wet himself, and everything about him, without necessity.”

By the early 1830s, Hawker was writing about the reputation of what we would come to know as the Labrador Retriever. It would be many years before the chance meeting between the 2nd Earl of Malmesbury and the 5th Duke of Buccleuch happened and the rest of the Lab’s story would play out, but between the written accounts by William Eppes Cormack and Hawker, breed historians suspect they may have a glimpse into the timeline of the early split.

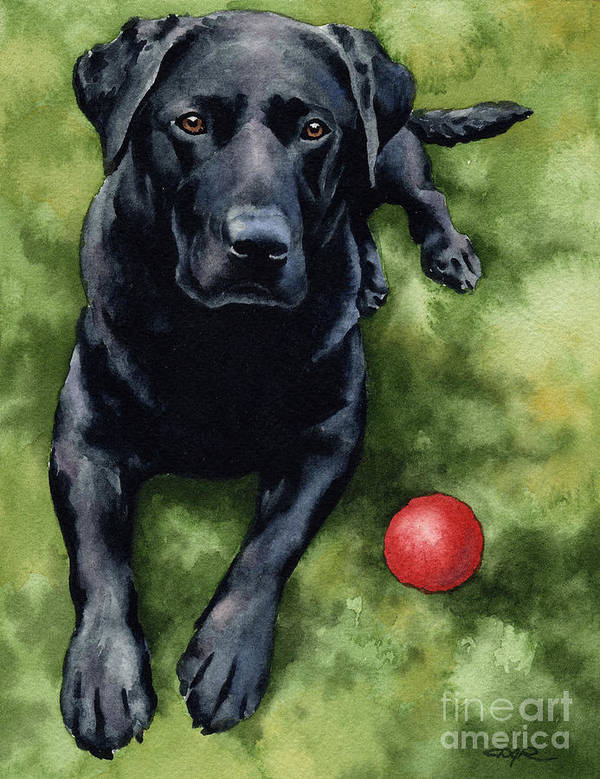

Image: Black Lab by David Rogers

DJ Rogers – k9artgallery

http://dogprintsgallery.com

www.etsy.com/shop/k9artgallery